Everything is just swell in Gazpromland, as long as you don’t dig too deep into the numbers and data.

Yesterday, Russia’s gas monopoly announced a first-quarter profit of 382 billion rubles (about $6 billion), lauding the 71 percent surge in profit compared to the same period in 2014. The only problem with this logic is that the “success” is calculated in Russian rubles, the world’s most volatile currency that is set for further devaluation as oil continues to slide into the abyss.

The seemingly massive jump in ruble terms actually equals a decrease in dollar value. The beleaguered ruble, which has lost 43 percent against the dollar in the last year, both helps and hinders the company. The upswing is that dollar and euro earnings account for a good chunk of the company’s revenue, and costs are mostly in rubles, and getting cheaper by the day. The downside is that the ricocheting ruble makes Gazprom investments risky.

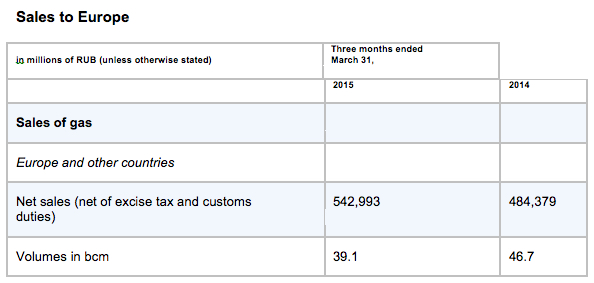

The most talked about point in the earnings report was the company’s sharp dropoff in sales to Europe, traditionally Gazprom’s biggest client.

The chart shows the company’s steep sales decline to Europe, Gazprom’s key export market that relies on Russia for one-third of its energy needs. Sales to Europe dropped to 39.1 billion cubic meters (bcm) in the first three months of 2015, compared to 46.7 percent during the same period last year. That’s more than a16 percent decrease.

Sales in Europe lag for a variety of reasons, but economic slowdown has cut deepest into demand, while the rise of sustainable energy on the continent continues to play a smaller role in Gazprom’s displacement in the market. Counting on economic growth in Europe in the future quarters would be more foolhardy than the company’s expensive pipeline to China, or its recent abortion of the South Stream project, which it had already invested $4.66 billion into the $29 billion project.

Russia sits on about 25 percent of the world’s gas reserves, and with the exception of a few pesky competitors, Gazprom has a monopoly both domestic production and export abroad.

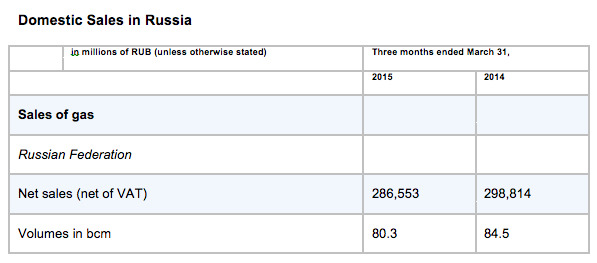

Gazprom is not only losing abroad but at home. In the first three months of 2015, it sold 80.3 bcm, 4.2 bcm less than in January-March of 2014. Independent producer Novatek and state-owned Surgutneftegas are chipping away at market share, along with a slew of other domestic producers.

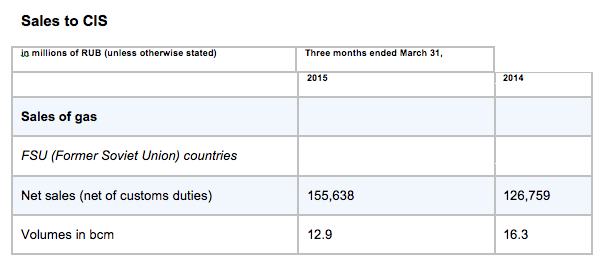

Russia is also failing to keep up with 2014 sales to former Soviet neighbors, especially Ukraine, one of Gazprom’s former bread and butter clients. Volume sales in the first quarter were down 20 percent.

If you want to check out the company’s full earnings report, it’s here.

Bad news for Gazprom is very evidently bad news for the Russian budget, which depends on the gas company for about 9 percent of the state’s budget. If the company doesn’t sell to its potential, the budget will face an even greater shortfall than already anticipated.

Back in 2008, when the company was valued at $360 million, Gazprom head Alexei Miller forecasted that within a decade the oil conglomerate would become the world’s largest company with a market capitalization of $1 trillion.

Now its market capitalization hovers around $51.5 billion. In the last year, stocks have lost more than 35 percent of their trading value.

In July, Russian business daily Vedomosti estimated that the company has wasted 2.4 trillion rubles (about $37.4 billion at the current exchange rate) on dead-end projects. The logic the newspaper provides is pretty rudimentary: Gazprom has a production capacity of 617 billion cubic meters, but will only produce 450 this year.

Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development has the number pegged even lower, at 414 bcm.

However, the bigger obstacle ahead for Gazprom isn’t what will happen next quarter, but rather in the long term: when cars run on hydrogen cells and not hydrocarbons, or when China develops to a point where it starts thinking about its environment and puts a pinch on its oil addiction.

And last but not least, let’s not forget about Gazprom’s tiff with the European Commission, which has formally launched an anti-trust case against the gas monopoly for being just that, a gas monopoly in Europe. If found guilty, Gazprom could face a fine of up to 10 percent of global yearly revenue. In 2013 was $164.62 billion, so the EU could hit the company with a more than $16 billion fine. So the one positive is that if Gazprom crashes and burns this year, it owes the EU less money.

Louise Dickson