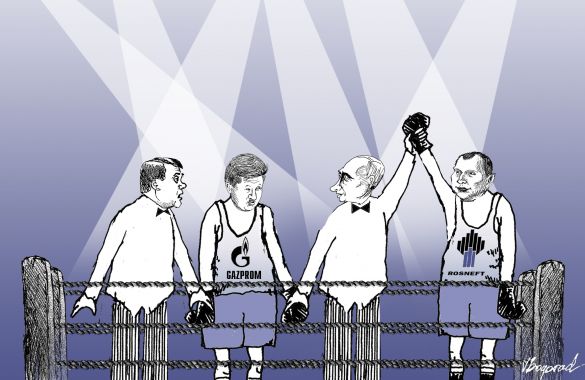

In Russia, state-controlled energy companies Rosneft and Gazprom have been in fierce competition with one another since the early 2000s, despite the fact one sells oil and the other natural gas. Whether fighting over big deals with China or licenses to explore the Arctic, the two colossal companies compete for the Kremlin’s favor.

On April 11, Rosneft’s market capitalization reached $51.7 billion, while Gazprom fell behind at $51.5 billion, Bloomberg reported. Ever since both companies declared themselves publicly-traded entities, Rosneft had always trailed Gazprom.

In 2008, Gazprom was valued at over $360 million, more than $250 million more than Rosneft. That year, Gazprom head Alexey Miller forecast that within a decade the oil conglomerate would become the world’s largest company with a market capitalization of $1 trillion. That didn’t exactly pan out. Now it’s worth $51.5 billion, and in 2015, stocks lost more than 35 percent of their trading value.

Chart from Bloomberg.com

Both monopolies are run by Putin associates from Petersburg. Igor Sechin, who Putin first met working under St. Petersburg mayor Anatoly Sobchak has been in charge of Rosneft since 2004 (more on the significance of this year later) and Alexey Miller has been at the helm of Gazprom since 2002. The two men are among Russia’s top paid CEOs.

Despite the slump in crude oil prices, Rosneft has been increasing assets and ramping up its international activities: it was the first Russian oil company to enter Iranian market and most recently began drilling its first deep-water project in Vietnam.

Lukoil produces its product more efficiently than Gazprom and has a much more liquid cash flow, despite the company’s massive debt from its $55 billion acquisition of TNK-BP in 2013.

Gazprom’s financial situation is precarious for a variety of reasons. Not only do LNG supplies threaten the inefficient behemoth’s market position, but Gazprom has to carry out the state’s political projects, even if they come at a loss.

Last July, business daily Vedomosti estimated Gazprom has wasted more than $35 billion in dead-end projects, with South Stream and Turkish Stream (both nixed over political reasons) being the most recent examples.

When Kiev turned away from Russian gas after Moscow sent troops into Eastern Ukraine, Gazprom missed out on $5.5 billion in revenues and fines.

If the Kremlin decides it is politically advantageous to give a gas discount to a particular country, Gazprom obliges. Most recently, Gazprom granted Armenia a discount, lowering the price of Russian gas from $165 per thousand cubic meters to $150.

Gazprom, which promises to a dividend return of 7.2 rubles per share this year, according to Deputy Chairman of the Management Board at Gazprom Andrey Kruglov, still faces a lawsuit from the European Commission for abusing its market dominance in Europe. The EC could fine Gazprom up to 10 percent of its global yearly revenue. Gazprom hasn’t reported its 2015 numbers, but based off 2014 figures, this would be about $16 billion.

Rosneft’s rise can be traced back to 2004, when Russia’s then largest oil company, Yukos, was cheaply sold off to Rosneft after Yukos head Mikhail Khodorkovsky was arrested on allegations of tax evasion.

One of the lesser-known aspects of the history is that Gazprom was originally the intended buyer of Yukos’ most valuable asset Yugankneftgaz, after it had merged with Rosneft, a deal Putin approved in September 2004. Gazprom was outmaneuvered by the virtually unknown Rosneft and its CEO Igor Sechin. The merger never happened.

While Khodorkovsky sat in a prison in Siberia, Igor Sechin began to rebuild his oil empire, but this time, under state supervision.

Earlier this year, Russia’s Federal Anti-Monopoly Service ruled that Gazprom was no longer allowed to call itself a “national treasure”.

Maybe Rosneft will take over the title?

Louise Dickson